Home >

If you spliced the genes of Hillary Clinton, Madonna, Heidi Fleiss and Margaret Thatcher, you might have someone like Victoria Woodhull.

- Steve Murray, review of the film America's Victoria

legal contender....

Victoria C. Woodhull -

first woman to run for president

a brief historical sketch by Susan Kullmann

On the 150th anniversary of her birth, September 23, 1988, Victoria Claflin Woodhull was largely lost to history. She still is. Few Americans even recognize her name. Yet "The Woodhull" was once one of the best known women in America -- the first woman to run for President and the first to open a bank on Wall Street. Nineteenth-century Americans thrilled to news stories about her exploits. Admirers pored over her weekly newspaper and scooped up her books, pamphlets, and photographs. Her lectures left thousands spellbound.

bewitching brokers

Woodhull worked under the assumption that a "woman's ability to earn money is better protection against the tyranny and brutality of men than her ability to vote." She and her younger sister Tennessee Claflin invaded Wall Street to achieve their economic independence. Newspapers hailed America's first female stockbrokers as "The Queens of Finance" and "The Bewitching Brokers." Susan B. Anthony applauded the arrival of women in Wall Street in 1870 as "a new phase of the woman's rights question."

Woodhull worked under the assumption that a "woman's ability to earn money is better protection against the tyranny and brutality of men than her ability to vote." She and her younger sister Tennessee Claflin invaded Wall Street to achieve their economic independence. Newspapers hailed America's first female stockbrokers as "The Queens of Finance" and "The Bewitching Brokers." Susan B. Anthony applauded the arrival of women in Wall Street in 1870 as "a new phase of the woman's rights question."

Woodhull, Claflin & Co., Bankers and Brokers, opened with the silent backing of America's wealthiest financier, railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt. Their earnings bankrolled Woodhull's presidential campaign and helped finance her newspaper. With this venture, Woodhull demonstrated her ability as a woman - a married mother of two - to "successfully engage in business."

Born in 1838, Woodhull witnessed the abolition of slavery and the birth of the dream of racial equality in America. Three months after invading Wall Street, she announced her intention to run for President in one of New York City's largest daily newspapers. When the thirty-one-year-old petticoat politician threw her cock's feather cap into the ring, men of color sat in Congress and several State legislatures. Sexual equality seemed as likely to her as women's liberation would appear a century later.

queens of the quill

The sister brokers launched Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly a month later. Initially published as a campaign sheet, the newspaper quickly took on a larger agenda. It evolved into a radical political, economic, and social open forum that shaped Woodhull's budding reform crusade. The sixteen-page weekly newspaper claimed twenty thousand subscribers and ran for six years.

The "Queens of the Quill" highlighted the lessons they learned on Wall Street. Muckrakers at heart, they published exposés on stock swindles, insurance frauds, and corrupt Congressional land deals. Reports of outrageous scams did not stop more reputable brokerage firms and banks from advertising on the Weekly's front page.

The "Queens of the Quill" highlighted the lessons they learned on Wall Street. Muckrakers at heart, they published exposés on stock swindles, insurance frauds, and corrupt Congressional land deals. Reports of outrageous scams did not stop more reputable brokerage firms and banks from advertising on the Weekly's front page.

Above all, the newspaper addressed issues that concerned women with unusual frankness. It advanced the editors' shared vision that women could live as men's equals in the work place, political arena, church, family circle, and bedroom. The words and deeds of ordinary and extraordinary women filled the Weekly's columns.

woman's rights advocate

Woodhull's experience as a lobbyist and businesswoman taught her how to penetrate the all-male domain of national politics. A year after she set up shop in Wall Street, she preempted the opening of the 1871 National Woman Suffrage Association's third annual convention in Washington. Suffrage leaders postponed their meeting to listen to the female broker address the House Judiciary Committee. Woodhull argued that women already had the right to vote - all they had to do was use it - since the 14th and 15th Amendments granted that right to all citizens. The simple but powerful logic of her argument impressed some committee members. Suffragists saw her as their newest champion. They applauded her statement: "women are the equals of men before the law, and are equal in all their rights."

Woodhull's experience as a lobbyist and businesswoman taught her how to penetrate the all-male domain of national politics. A year after she set up shop in Wall Street, she preempted the opening of the 1871 National Woman Suffrage Association's third annual convention in Washington. Suffrage leaders postponed their meeting to listen to the female broker address the House Judiciary Committee. Woodhull argued that women already had the right to vote - all they had to do was use it - since the 14th and 15th Amendments granted that right to all citizens. The simple but powerful logic of her argument impressed some committee members. Suffragists saw her as their newest champion. They applauded her statement: "women are the equals of men before the law, and are equal in all their rights."

Woodhull catapulted to the leadership circle of the suffrage movement with her first public appearance as a woman's rights advocate. Although her Constitutional argument was not original, she focused unprecedented public attention on suffrage. Following Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Woodhull was the second woman to petition Congress in person. Newspapers reported her appearance before Congress. The Time magazine of its day, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, printed a full-page engraving of Woodhull, surrounded by prominent suffragists, as she delivered her argument.

queen of the rostrum

Woodhull invigorated the Cause and became one of the movement's most articulate speakers. Her Lecture on Constitutional Equality attracted thousands. Newspapers cited her as "the ablest advocate on Woman Suffrage, a woman of remarkable originality and power." When the Judiciary Committee issued a minority report supporting Woodhull's position, suffragists distributed thousands of copies throughout the nation.

contemporary supporters and critics

For the most part, those who knew Woodhull personally were willing to accept her "money and brains and unceasing energy" for the Cause. Susan B. Anthony, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Belva Lockwood, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women's rights leaders befriended her, some for the rest of their lives. Others were offended by her clairvoyant practices, her divorce from her first husband, and the peculiar extended family that she supported in her fashionable Manhattan mansion.

Bestselling author Harriet Beecher Stowe was her most renowned critic. Chagrined by Woodhull's magnetic blue eyes, rural Ohio speech, and "indelicate" style and behavior, Stowe spoofed her as Miss Audacia Dangereyes, the "advanced woman of the period." In her novel My Wife and I, the wife applauds her father when he lambasts the idea of a woman running for President with the sentiment:

"...no woman that was not willing to be dragged through every kennel, and slopped into every dirty pail of water, like an old mop, would ever consent to run as a candidate. Why it's an ordeal that kills a man. And what sort of a brazen tramp of a woman would it be that could stand it, and come out of it without being killed? Would it be any kind of a woman that we should want to see at the head of our government?"

In response to being judged by different standards than male politicians and reformers, Woodhull intensified and expanded her reform agenda.

In response to being judged by different standards than male politicians and reformers, Woodhull intensified and expanded her reform agenda.

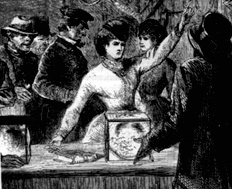

With Constitution in hand, the Queens of Finance attempted to vote in the 1871 elections. Though turned away from the polls, their effort inspired nationally-circulated Harper's Weekly to print a half-page illustration showing "Mrs. Woodhull Asserting Her Right to Vote."

bourgeois feminist

A month after the "Queens of the Quill" attempted to vote, their Weekly provided the public with the first English translation of Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto published in America. The editors tried to demonstrate their ability to lead the American branch of Marx's First International Workingmen's Association. Ironically, not Wall Street profits but the sisters' devotion to equality between the sexes prompted Marx's London Council to throw Woodhull and Claflin out of the IWA.

"free lover"

Woodhull's suffrage lecture marked the beginning of a public speaking career that spanned the next few decades. The "Queen of the Rostrum" spoke about women's rights, finance, labor and capital, spiritualism, and sexual relations. Her most popular lectures focused on what she called "social freedom." Sensitized by her own divorce from the alcoholic she married at the age of fourteen, Woodhull denounced legal and religious arguments for enduring a rotten marriage. She compared social freedom to freedom of religion. While she claimed to be a "monogamist," Woodhull defended the right of others to decided what later generations would call their own lifestyles.

Woodhull's suffrage lecture marked the beginning of a public speaking career that spanned the next few decades. The "Queen of the Rostrum" spoke about women's rights, finance, labor and capital, spiritualism, and sexual relations. Her most popular lectures focused on what she called "social freedom." Sensitized by her own divorce from the alcoholic she married at the age of fourteen, Woodhull denounced legal and religious arguments for enduring a rotten marriage. She compared social freedom to freedom of religion. While she claimed to be a "monogamist," Woodhull defended the right of others to decided what later generations would call their own lifestyles.

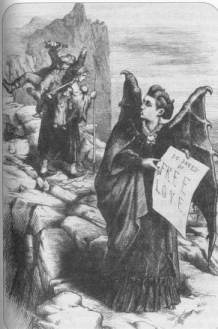

Irritated by her social freedom lecture, popular cartoonist Thomas Nast lampooned Woodhull as "Mrs. Satan" in a full-page engraving for Harper's Weekly. Nast's cartoon showed a tired, ragged young woman walking along the edge of a rocky cliff with babe in arms. She carries another child and her drunk husband on her back. A demonic Victoria Woodhull, horned and winged, holds a sign up to the woman: "BE SAVED BY FREE LOVE." The wife's response: "Get thee behind me, (Mrs.) Satan! I'd rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow your footsteps."

Woodhull's message struck a chord in some hearts. One of the largest public assemblies in New York's history, some 3000, was "cordially disappointed at the high moral ground and limited license which the speaker's definition of Freedom would allow." In Boston, Woodhull was "listened to with deference, encouraged with much applause, and retired with the verdict of all that she had spoken much truth." The Pittsburgh Dispatch called her "the most prominent woman of our time." Two months later, Woodhull presented the keynote speech at a national suffrage convention.

presidential campaign

During all this, Woodhull pursued her Presidential campaign. She published a 250-page collection of essays that spelled out her position on the problems facing the nation. A leading writer and reformer, Theodore Tilton, wrote Woodhull's authorized campaign biography. She had a comprehensive platform, two campaign committees, a campaign button, and a bona fide nominating convention. She challenged incumbent Ulysses S. Grant and his Democratic opponent Horace Greeley. Her running mate was abolitionist leader and social reformer Frederick Douglass.

The Equal Rights Party selected her as their standard bearer six months after Woodhull first delivered her social freedom speech. Their convention stands as the largest, most representative third party gathering of the 1872 election. Fifteen hundred men and women lent their voices to Woodhull's nomination by acclamation.

The Equal Rights Party selected her as their standard bearer six months after Woodhull first delivered her social freedom speech. Their convention stands as the largest, most representative third party gathering of the 1872 election. Fifteen hundred men and women lent their voices to Woodhull's nomination by acclamation.

Woodhull's support came from suffragists, land and labor reformers, peace and temperance people, Internationalists, and spiritualists. The Equal Rights Party platform supported women's right to vote, work, and love freely; nationalization of land; cost-based pricing to reduce excessive profits; a fairer division of earnings between labor and capital; the elimination of exorbitant interest rates; and free speech and a free press.

Practical movements, Woodhull learned, alarm "cowardly hearts" more than speeches and publications. Her "impending revolution" was quashed soon after the convention. Unforeseen reprisals devastated her personal life, business, and reform activities. Unable to secure housing in Manhattan, she and her family spent weeks sleeping on the floor of her newspaper office. Her twelve-year-old daughter assumed an alias to attend school without harassment. Financial difficulties forced the suspension of Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly for four months.

the Beecher-Tilton scandal

The newspaper resumed publication with an acerbic revelation of the editors' personal and financial difficulties. Renewing the crusade against hypocrisy in high places, the Weekly printed two explicit exposés. One detailed the extramarital affairs of Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, who cuckolded his friend, colleague, and parishioner, writer Theodore Tilton - Woodhull's first biographer. The other focused on a licentious stockbroker, Luther Challis, who boasted about his conquests of innocent young girls. The "scandal issue" created a national sensation.

In an ironic twist of fate, the first woman to run for President spent Election Eve behind bars. Reverend Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe's younger brother, was one of the nation's most prominent clergymen. His supporters retaliated quickly. Woodhull and Claflin were arrested for using the U.S. mails to "utter obscene publication" in the Challis article. Woodhull described her arrest as an attempt by the government to "establish a precedent for the suppression of recalcitrant Journals."

The Queens of the Quill became the targets of one of YMCA reformer Anthony Comstock's earliest censorship campaigns. They spent weeks in various New York City jails, paid more bail - over $60,000 for an alleged misdemeanor - than Tammany Hall's corrupt "Boss" Tweed, and faced charges related to the scandal issue for nearly two years. Their defense of themselves and the Bill of Rights reached the public through the Weekly and Woodhull's public lectures. The sisters were found innocent on the obscenity counts in 1873, and innocent of libel in the Challis article in 1874.

Victoria Claflin Woodhull Martin's legacy

Burned out, Woodhull and Claflin moved to England a few years later. They remained there for the rest of their lives. Both married wealthy men and lived comfortably into the twentieth century. They lectured occasionally and continued to publish. Their zealous reform spirit never recovered to pre-scandal heights.

Victoria Woodhull promoted changes that frightened, embarrassed, or in some cases delighted her contemporaries. She challenged several male-dominated organizations and institutions. She attempted to change society's views about sexuality and family structure. She tried to use existing law and the political system to achieve a more egalitarian society, and felt the brunt of the establishment when she overstepped propriety and subjected social relations to the same kind of muckraking she used to expose unethical business practices.

Victoria Woodhull promoted changes that frightened, embarrassed, or in some cases delighted her contemporaries. She challenged several male-dominated organizations and institutions. She attempted to change society's views about sexuality and family structure. She tried to use existing law and the political system to achieve a more egalitarian society, and felt the brunt of the establishment when she overstepped propriety and subjected social relations to the same kind of muckraking she used to expose unethical business practices.

Women who threaten patriarchal institutions are particularly vulnerable to being obscured and misunderstood. Her opponents - and there were many - discredited Woodhull and the issues she raised about sexual politics in nineteenth-century America. With few exceptions, historians ignore Woodhull or question her sincerity. Many writers emphasize her notoriety to the point of overshadowing her serious abilities, her notable accomplishments, and her provocative dreams.

Victoria Woodhull's comet-like career as an American social reformer may have been unequaled by her contemporaries in its scope, in its intensity, and in its visions of equality and justice. Hers is a legacy worth reclaiming.

© 1997 Susan Kullmann (Puz). This article first appeared in The Women's Quarterly (Fall 1988), pp. 16-17. Research for the article was conducted at the Huntington Library, the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, the New York Historical Society, the Boston Public Library, and the Homer, Ohio Public Library.